CD is a 50-year-old male presenting to your ambulatory care clinic to discuss vaping cessation. About three years ago, CD stopped smoking combustible tobacco cigarettes by transitioning to electronic cigarettes. Recently, he’s seen news articles about the unknown long-term health effects of vaping and is curious if there is a medication to help him quit. We currently don’t have any vaping cessation guidelines, but we will explore what evidence we have to help patients with this issue.

Tobacco Product Background

In 2021, an estimated 46 million (18.7%) U.S. adults used tobacco products with the most common product being combustible tobacco cigarettes (28.3 million, 11.5%), followed by electronic cigarettes (11.1 million, 4.5%). Compared to 2020, the prevalence of cigarette smoking decreased from 12.5%, while the prevalence of e-cigarette use increased from 3.7%.

This increase in e-cigarette use is likely multifactorial and affected by people using e-cigarettes for tobacco smoking cessation, to relieve cigarette withdrawal symptoms, for affordability compared to cigarettes, to cause less harm to others, and for the enjoyment of the continued “smoking” experience.

Pharmacotherapy for Tobacco Cigarette Cessation

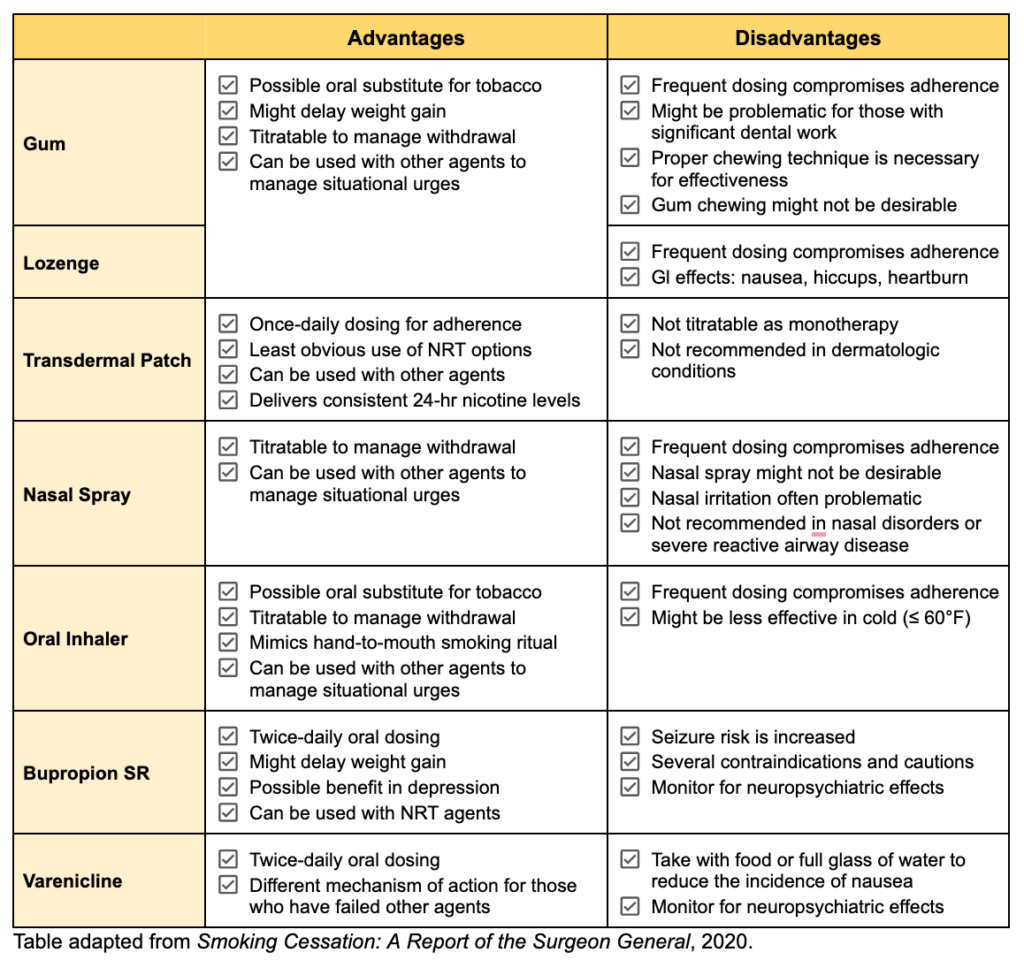

The 2021 USPSTF Guidelines state that effective tobacco cessation interventions should include pharmacotherapy and/or behavioral counseling. To date, there are three types of pharmacotherapy approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of tobacco use disorder: nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) (including nicotine gum, lozenges, transdermal patches, nasal spray, and oral inhalers), bupropion SR, and varenicline. Unfortunately, the USPSTF does not provide vaping cessation guidelines.

All seven pharmacotherapy agents are considered first-line and increase the rates of smoking cessation; however, a handful of small studies have shown varenicline to be superior to both NRT and bupropion. The 2020 American Thoracic Society Guidelines even recommend varenicline (great board exam question!) over the nicotine patch or bupropion, as a strong recommendation with moderate certainty in the estimated effects. Regardless, cessation therapy should be tailored to the specific patient.

The potential advantages and disadvantages of each pharmacotherapy are outlined in the following table.

Pharmacotherapy for Vaping (E-cigarette) Cessation?

There are tons of clinical guidelines out there to help providers and patients navigate tobacco cigarette cessation, but is there any clinical guidance for e-cigarette cessation? Currently, we are not aware of any vaping cessation guidelines but there is some evidence for using pharmacotherapy for vaping cessation.

Varenicline For Vaping Cessation

Just last year, Caponnetto et al. (2023) published a randomized placebo-controlled trial looking at the efficacy and safety of varenicline plus behavioral counseling for vaping cessation. To be included in this study, participants had to be at least 18 years of age, exclusively use e-cigarettes daily, have attempted to quit in the past, and be willing to quit at present. A total of 140 participants were randomly assigned to receive counseling plus varenicline dosed at 1 mg twice daily or matching placebo. The treatment phase was 12 weeks, followed by a subsequent 12-week non-treatment follow-up phase. What is interesting about this study is the authors utilized the saliva cotinine level-verified continuous abstinence rate (CAR) at weeks 4 to 12 as their primary efficacy endpoint (cotinine is a metabolite of nicotine and can be measured in saliva, urine, or blood to detect the use of nicotine and/or tobacco). The authors found that the CAR was higher in the varenicline group (40.0%) compared to placebo (20.0%) at each interval: weeks 4-12 (OR 2.67; 95% CI, 1.25 to 5.68; P = 0.011). However, there was a significantly higher rate of adverse events in the varenicline group vs. the placebo group (246 vs. 154; P = 0.042) which included nausea, flatulence, and abnormal dreams. These adverse events were generally mild-to-moderate in severity and rarely led to treatment discontinuation.

Despite these compelling results, the authors acknowledge several limitations to the generalizability of their study results. First, the study population was generally middle-aged, so the results may not apply to younger e-cigarette users. Second, the participants in this study exclusively used e-cigarettes and possessed a strong desire to quit, so it is unclear what the effects of varenicline may be in a population who may smoke tobacco and use e-cigarettes or is uninterested in quitting. Third, the varenicline and placebo groups were not well-matched for anxiety and e-cigarette dependence levels. The significantly higher levels of anxiety and e-cigarette dependence in the placebo groups may have acted as confounders of the study.

Nicotine Replacement Therapy

Compared to varenicline, the data to support the use of NRT in vaping cessation is lacking. The current literature includes small, underpowered pilot studies (Palmer et al., 2023, Sahr et al., 2021) and single-patient case reports (Silver et al., 2016) that have typically extrapolated tobacco cigarette-specific recommendations to patients attempting to quit vaping.

Several guidelines and well-conducted studies exist to guide the clinical use of pharmacotherapy for tobacco smoking cessation. Until recently, there has been a paucity of evidence to support pharmacotherapy for e-cigarette cessation. New clinical trial data suggests that varenicline is superior to placebo for achieving e-cigarette abstinence, but additional studies are still warranted.

Are you aware of any other evidence regarding vaping cessation guidelines?

This article was written by Kaitlyn Nichols, PharmD Candidate in collaboration with Eric Christianson, PharmD, BCPS, BCGP

References:

- Caponnetto P, Campagna D, Ahluwalia JS, et al. Varenicline and counseling for vaping cessation: a double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Med. 2023;21(1):220.

- Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Jamal A, et al. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults — United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:475-483.

- Leone FT, Zhang Y, Evers-Casey S, et al. Initiating Pharmacologic Treatment in Tobacco-Dependent Adults. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(2):e5-e31.

- Palmer AM, Carpenter MJ, Rojewski AM, et al. Nicotine replacement therapy for vaping cessation among mono and dual users: A mixed methods preliminary study. Addict Behav. 2023;139:107579.

- Sahr M, Kelsh S, Blower N, et al. Pilot Study of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS) Cessation Methods. Pharmacy (Basel). 2021;9(1):21.

- Silver B, Ripley-Moffitt C, Greyber J, et al. Successful use of nicotine replacement therapy to quit e-cigarettes: lack of treatment protocol highlights need for guidelines. Clin Case Rep. 2016;4(4):409-411.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Smoking Cessation. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2020.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Krist AH, Davidson KW, et al. Interventions for Tobacco Smoking Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Persons: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021;325(3):265-279.

- Yong HH, Borland R, Cummings KM, et al. Reasons for regular vaping and for its discontinuation among smokers and recent ex-smokers: findings from the 2016 ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey. Addiction. 2019;114 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):35-48.

0 Comments